Silver is a white metallic element, harder than gold, softer than copper and second only to gold in malleability and ductility. Represented on the Periodic Table of the Elements by the symbol Ag, silver is an excellent conductor of heat and electricity. Silver is considered one of the noble metals because of its excellent resistance to oxidation. Historically, silver has played a prominent role in the production of jewelry and objets d’art and is usually alloyed with another metal to harden it enough to maintain the desired shape and details imparted to it.

Silver Significance

Silver is relatively inexpensive today when you compare it to other precious metals like gold or platinum. This could lure one into believing that it isn’t an important metal. That is a false assumption! At times throughout history silver was valued more highly than gold. When you examine the quantities of silver used in jewelry, its use outweighs all other precious metals by a large factor. This versatile white metal also triggered far more technological advances in the field of mining and metallurgy than its other precious metallic cousins. Entire economies have depended on its availability and the access to silver deposits has swung wars and as a result history. Silver is without a doubt one of the most important metals in use by mankind.

Bronze Age Silver

Mesopotamia

Our silver story starts somewhere at the end of the 4th millennium BC when clever inhabitants of modern-day Turkey figured out they could extract silver from lead through cupellation (see also: Silver Mining & Metallurgy). Very few silver pieces from this time have survived but those that do give us a great insight in what these Bronze Age silversmiths were capable of.

At the dawn of history (history meaning that part of the past we have written accounts of) silver was used as a currency in Mesopotamia. Not as in coins but purely by weight or in the form of rings. The Mesopotamian silversmith’s shop would have resembled that of the goldsmith or, as is often the case these days, would have been the very same shop. Although silver is slightly less ductile than gold and requires more frequent annealing during the manufacturing process it can still be cast, hammered into extremely thin sheets, engraved, embossed, used in repoussé work and decorated with filigree and granulation. Vessels, statuettes, and jewelry have been found which indicate that silver with high purity was used, yielding quite soft objects.

Egypt

© The Trustees of the British Museum

The Egyptians cherished the rare and exotic. When it came from far away, they loved it. Great lengths of trouble were gone through to get Afghan Lapis lazuli, arguably the most valuable gemstone to them. Along this trade route, silver reached Egypt as well and, just as with lapis, it was valued highly and seen as extremely exclusive. Gold could be obtained close to home from the mountains in the Eastern Desert and Nubia. Perhaps some electrum has come from here as well but pure silver must have been imported, causing it to be worth more than gold and only fit for the most important people.

By about 1600 BC the value of silver had sunk to about half that of gold, indicating that the supply of the metal had grown considerably. By this time it was used as an abstract currency having a constant value. The popularity of silver apparently was submitted to the conjuncture of fashion. King Tut’s grave, for instance, contained hardly any silver items while Sheshonq II even had an all-silver sarcophagus.

Minoa, Mycenae & Phoenicia

The Minoans, and to a greater extent, the later Mycenaeans were traders and consequently would have dealt with silver a lot. Hence, we do see a considerable amount of early Greek silver jewelry from archaeological sites on the Greek mainland, Crete, and Cyprus.

The Phoenicians played a special role in the development of the Mediterranean civilizations through their colonization and trade with all corners of the area. It was the Phoenicians who started the exploitation of the Spanish silver deposits and distribution throughout the classical world. Their incentives pulled silver from its exclusive and exotic status and its availability rose to levels never seen before.

Classical Silver

To both the Greek and Roman societies the availability of silver was extremely important as their currencies, properly minted silver coins, depended on it. It appears that it wasn’t used in jewelry as much as gold was (we see way more gold items surviving from that era) but to some extent, this may be due to remelting and recycling. That which survived shows that it was used for all possible types of jewelry, finger rings, anklets, armlets, etc.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

© The Trustees of the British Museum

The Romans were fond of niello which is a surface decoration technique very similar to enameling but done with silver sulfate rather than glass. Niello is much tougher than enamel and has a metallic luster rather than a vitreous one. During the Roman occupation of Northern Europe, niello spread throughout the continent, as can be seen from Anglo-Saxon finds in Britain, as well as in Eastern Europe.

Reading Pliny is always good for a nice insight into Roman life through the eyes of an incredible skeptic. Below follow a few chapters from his Naturalis Historia concerning silver and the Roman fondness for it:

Chapter 31. Silver.

After stating these facts, we come to speak of silver ore, the next (after gold) folly of mankind. Silver is never found but in shafts sunk deep in the ground, there being no indications to raise hopes of its existence, no shining sparkles, as in the case of gold. The earth in which it is found is sometimes red, sometimes of an ashy hue. It is impossible, too, to melt it, except in combination with lead or with galena, this last being the name given to the vein of lead that is mostly found running near the veins of the silver ore. When submitted, too, to the action of fire, part of the ore precipitates itself in the form of lead, while the silver is left floating on the surface, like oil on water.Silver is found in nearly all our provinces, but the finest of all is that of Spain; where it is found, like gold, in uncultivated soils, and in the mountains even. Wherever, too, one vein of silver has been met with, another is sure to be found not far off: a thing that has been remarked, in fact, in the case of nearly all the metals, which would appear from this circumstance to have derived their Greek name of “metalla.” It is a remarkable fact, that the shafts opened by Hannibal in the Spanish provinces are still worked, their names being derived from the persons who were the first to discover them. One of these mines, which at the present day is still called Bæbelo, furnished Hannibal with three hundred pounds’ weight of silver per day. The mountain is already excavated for a distance of fifteen hundred paces; and throughout the whole of this distance there are water-bearers standing night and day, baling out the water in turns, regulated by the light of torches, and so forming quite a river.

The vein of silver that is found nearest the surface is known by the name of “crudaria.” In ancient times, the excavations used to be abandoned the moment alum was met with, and no further search was made. Of late, however, the discovery of a vein of copper beneath alum, has withdrawn any such limits to man’s hopes. The exhalations from silver-mines are dangerous to all animals, but to dogs more particularly. The softer they are, the more beautiful gold and silver are considered. It is a matter of surprise with most persons, that lines traced with silver should be black.

Chapter 44. The different kinds of silver, and the modes of testing it.

There are two kinds of silver. On placing a piece of it upon an iron fire-shovel at a white heat, if the metal remains perfectly white, it is of the best quality: if again it turns of a reddish colour, it is inferior; but if it becomes black, it is worthless. Fraud, however, has devised means of stultifying this test even; for by keeping the shovel immersed in men’s urine, the piece of silver absorbs it as it burns, and so displays a fictitious whiteness. There is also a kind of test with reference to polished silver: when the human breath comes in contact with it, it should immediately be covered with steam, the cloudiness disappearing at once.

Chapter 49. Instances of luxury in silver plate.

The caprice of the human mind is marvellously exemplified in the varying fashions of silver plate; the work of no individual manufactory being for any long time in vogue. At one period, the Furnian plate, at another the Clodian, and at another the Gratian, is all the rage—for we borrow the shop even at our tables. Now again, it is embossed plate that we are in search of, and silver deeply chiselled around the marginal lines of the figures painted upon it; and now we are building up on our sideboards fresh tiers of tables for supporting the various dishes. Other articles of plate we nicely pare away, it being an object that the file may remove as much of the metal as possible.

We find the orator Calvus complaining that the saucepans are made of silver; but it has been left for us to invent a plan of covering our very carriages with chased silver, and it was in our own age that Poppæa, the wife of the Emperor Nero, ordered her favourite mules to be shod even with gold!

Chapter 50. Instances of the frugality of the ancients in reference to silver plate.

The younger Scipio Africanus left to his heir thirty-two pounds’ weight of silver; the same person who, on his triumph over the Carthaginians, displayed four thousand three hundred and seventy pounds’ weight of that metal. Such was the sum total of the silver possessed by the whole of the inhabitants of Carthage, that rival of Rome for the empire of the world! How many a Roman since then has surpassed her in his display of plate for a single table! After the destruction of Numantia, the same Africanus gave to his soldiers, on the day of his triumph, a largess of seven denarii each—and right worthy were they of such a general, when satisfied with such a sum! His brother, Scipio Allobrogicus, was the very first who possessed one thousand pounds’ weight of silver, but Drusus Livius, when he was tribune of the people, possessed ten thousand. As to the fact that an ancient warrior, a man, too, who had enjoyed a triumph, should have incurred the notice of the censor for being in possession of five pounds’ weight of silver, it is a thing that would appear quite fabulous at the present day. The same, too, with the instance of Catus Ælius, who, when consul, after being found by the Ætolian ambassadors taking his morning meal off of common earthenware, refused to receive the silver vessels which they sent him; and, indeed, was never in possession, to the last day of his life, of any silver at all, with the exception of two drinking-cups, which had been presented to him as the reward of his valour, by L. Paulus, his father-in-law, on the conquest of King Perseus.

We read, too, that the Carthaginian ambassadors declared that no people lived on more amicable terms among themselves than the Romans, for that wherever they had dined they had always met with the same silver plate. And yet, by Hercules! to my own knowledge, Pompeius Paulinus, son of a Roman of equestrian rank at Arelate, a member, too, of a family, on the paternal side, that was graced with the fur, had with him, when serving with the army, and that, too, in a war against the most savage nations, a service of silver plate that weighed twelve thousand pounds!

Chapter 51. At what period silver was first used as an ornament for couches.

For this long time past, however, it has been the fashion to plate the couches of our women, as well as some of our ban- quetting-couches, entirely with silver. Carvilius Pollio, a Roman of equestrian rank, was the first, it is said, to adorn these last with silver; not, I mean, to plate them all over, nor yet to make them after the Delian pattern; the Punic fashion being the one he adopted. It was after this last pattern too, that he had them ornamented with gold as well: and it was not long after his time that silver couches came into fashion, in imitation of the couches of Delos. All this extravagance, however, was fully expiated by the civil wars of Sulla.

Chapter 53. The enormous price of silver plate.

It is not, however, only for vast quantities of plate that there is such a rage among mankind, but even more so, if possible, for the plate of peculiar artists: and this too, to the exculpation of our own age, has long been the case. C. Gracchus possessed some silver dolphins, for which he paid five thousand sesterces per pound. Lucius Crassus, the orator, paid for two goblets chased by the hand of the artist Mentor, one hundred thousand sesterces: but he confessed that for very shame he never dared use them, as also that he had other articles of plate in his possession, for which he had paid at the rate of six thousand sesterces per pound. It was the conquest of Asia that first introduced luxury into Italy; for we find that Lucius Scipio, in his triumphal procession, exhibited one thousand four hundred pounds’ weight of chased silver, with golden vessels, the weight of which amounted to one thousand five hundred pounds. This took place in the year from the foundation of the City, 565. But that which inflicted a still more severe blow upon the Roman morals, was the legacy of Asia, which King Attalus left to the state at his decease, a legacy which was even more disadvantageous than the victory of Scipio, in its results. For, upon this occasion, all scruple was entirely removed, by the eagerness which existed at Rome, for making purchases at the auction of the king’s effects. This took place in the year of the City, 622, the people having learned, during the fifty-seven years that had intervened, not only to admire, but to covet even, the opulence of foreign nations. The tastes of the Roman people had received, too, an immense impulse from the conquest of Achaia, which, during this interval, in the year of the City, 608, that nothing might be wanting, had introduced both statues and pictures. The same epoch, too, that saw the birth of luxury, witnessed the downfall of Carthage; so that, by a fatal coincidence, the Roman people, at the same moment, both acquired a taste for vice and obtained a license for gratifying it.

Some, too, of the ancients sought to recommend themselves by this love of excess; for Caius Marius, after his victory over the Cimbri, drank from a cantharus, it is said, in imitation of Father Liber; Marius, that ploughman of Arpinum, a general who had risen from the ranks!

Chapter 55. The most remarkable works in silver.

It is a remarkable fact that the art of chasing gold should have conferred no celebrity upon any person, while that of embossing silver has rendered many illustrious. The greatest renown, however, has been acquired by Mentor, of whom mention has been made already. Four pairs [of vases] were all that were ever made by him; and at the present day, not one of these, it is said, is any longer in existence, owing to the conflagrations of the Temple of Diana at Ephesus and of that in the Capitol. Varro informs us in his writings that he also was in possession of a bronze statue, the work of this artist. Next to Mentor, the most admired artists were Acra- gas, Boëthus, and Mys. Works of all these artists are still extant in the Isle of Rhodes; of Boëthus, in the Temple of Minerva, at Lindus; of Acragas, in the Temple of Father Liber, at Rhodes, consisting of cups engraved with figures in relief of Centaurs and Bacchantes; and of Mys, in the same temple, figures of Sileni and Cupids. Representations also of the chase by Acragas on drinking cups were held in high estimation.

All at once, however, this art became so lost in point of excellence, that at the present day ancient specimens are the only ones at all valued; and only those pieces of plate are held in esteem the designs on which are so much worn that the figures cannot be distinguished.

Silver becomes tainted by the contact of mineral waters, and of the salt exhalations from them, as in the interior of Spain, for instance.

Celtic Silver

To the Celtic tribes, silver together with bronze was used extensively for jewelry. Decorated brooches, torcs, and lunulae were the most common type of jewelry. Before the Roman invasion, the Celts didn’t use coinage but instead used ‘ring money’. These rings were of silver, copper, bronze, or gold and weren’t intended for wearing but were solely used as a currency.

Medieval Silver

With the downfall of the Roman supply lines, gold became a rarity in Europe. As a consequence silver became the foremost metal used for jewelry. Germanic jewelry consisted mainly of functional items such as fibulae, disc brooches, penannular brooches, and buckles, often made of silver and sometimes gilded or inlaid with precious stones with garnets being the most popular choice by far.

From around 800AD on, Viking conquest along the northwest European coast caused enormous amounts of silver to be carted to Scandinavia where silversmiths flourished and silver jewelry became a tradition. The discovery of the Swedish silver deposits somewhere around the turn of the first millennium certainly fueled the custom of wearing silver.

Niello‘s popularity with the Romans had been transferred to the Germanic tribes, the black-white color combination being used to give optimal contrast to the typical Germanic engraving patterns.

©Trustees of the British Museum.

The Fuller Brooch

Description by the British Museum:

Circular brooch of hammered sheet-metal, slightly convex in section. It is extensively inlaid with niello and has an open-work outer zone encircling a central roundel which is framed and divided by broad milled borders, into a central lozenge shape surrounded by four subsidiary lentoid fields. These are punctuated at the four points of intersection by bosses, with a fifth at the centre; three of these conceal rivets attaching the (lost) pin mechanism behind.The decorative scheme consists of personifications of the Five Senses in the central roundel, surrounded by the openwork zone of smaller roundels containing alternating geometric animal and human motifs symbolising the different aspects of Creation in a not-quite-symmetrical arrangement. The large central field is occupied by a three-quarter length personification of Sight, with large oval eyes. In each hand he holds a drooping foliate spray with double nicked details; above his head is a three-staged leaf, and on either side of it a triquetra. The points of the lozenge, each with a domed rivet, touch the border of the circular field, creating four lenticular panels, each with a full-length human figure depicting one of the other Senses. They wear short jackets and belted tunics. Any background space remaining is filled with an assortment of foliate scrolls or interlace. In the upper left panel is Taste, with one hand in his mouth, the other holding a foliate stem, while profiled Smell, in the top right, is flanked by two plants, and has his hands behind his back. Touch, in the bottom right panel, places his hands together, and Hearing, in the bottom left, appears to be running, and cupping his hand to his ear. Everything is set upon a nielloed ground. The back is plain and the pin mechanism is now missing. Two small holes at the top may have been for suspension. © Trustees of the British Museum.

As society developed and trade routes to the east were re-established gold retook its old position of being the most popular metal for fine jewelry again. Nevertheless, it was this same trade that allowed a large middle class to develop whose members started to adorn themselves in a way that was previously only reserved for wealthy rulers. Those on a budget would opt for silver jewelry as it was more affordable.

The versatility of jewelry increased, moving away from mainly functional items towards purely decorative and, to a large extent, symbolic items. Finger rings, bangles, pendants, etc. all returned to the jewelry stage and were executed in silver.

By the end of the Middle Ages, silver jewelry and silverware became submissive to hallmarking. See Silver Assaying & Hallmarking.

Renaissance Silver

The era we call the Renaissance conventionally runs from 1500 to 1600 but as a style the Renaissance has its origin at the end of the 13th century in Northern Italy. Trade with the Levant intensified over the last two centuries of the Middle Ages. The European population recovered after its decimation by the plague and there was an expansion of trade centers in the Northern coastal areas like the Netherlands. Here a large middle class developed and cities grew exponentially.

The Byzantine Empire fell in 1453, and many exiles from the areas now controlled by the Ottoman Turks fled to Europe, bringing knowledge that had been forgotten through the Middle Ages. Italy became the center for many developments, having wealth from trade with Asia and Europe, as well as the power of the Church.

Following the discovery of America, a great age of exploration followed. Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, French, and English explorers fought to claim the world for their countries. Christopher Columbus led Spain to the forefront of world exploration when he claimed the Americas for Spain. Portugal and Spain are the front-runners in the New World for this century, which included Pizarro’s subjugation of the Incas and Cortez’s similar conquest of the Aztecs. Silver mines provided vast amounts of silver for trade from 1546 on when significant deposits were found in modern-day Mexico. Some of this went directly from South America to China, to secure Asian items.1

Silver working techniques remained the same as in medieval times, the big difference with the preceding era was the availability of silver which was brought to Europe in large quantities from the Americas. With a growing population and level of prosperity in Europe, this was a welcome event that allowed silver to remain to be used as a currency and (relatively) affordable as a precious metal for jewelry.

Baroque Silver

The Baroque period, spanning from around 1600 to 1700, saw an increasing amount of South American silver being brought to Europe. The English, French, and Dutch all established bases in the New World. The Netherlands, now independent from Spain, is a major player on the world’s stage, and the artists from the Low Countries dominate not just the Art World but also the Atlantic through their superior navy. Many battles with the Spanish and English navies were fought, often over rich loads of silver on board ships returning from the New World.

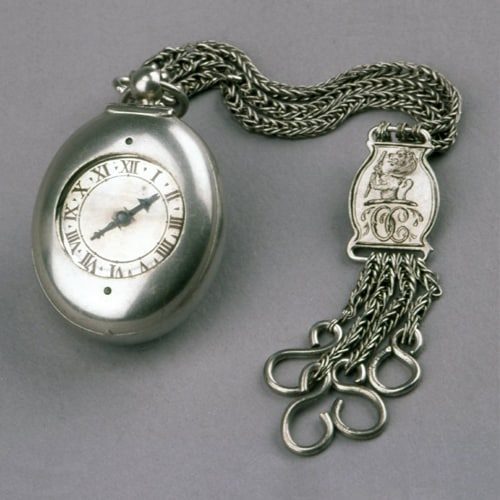

Although silver working techniques remained the same as in the preceding centuries a few things did change. Timepieces were a complete novelty and were often executed in silver. Another novelty was the use of silver to set diamonds. The white metal complimented the absence of color in these stones which were now trickling into Europe through intensified trade with India after European sailors started settlements on the Indian peninsula. This enabled them to conduct direct trade with Indian diamond dealers in contrast to earlier times when Arabic merchants acted as middlemen and few good diamonds reached Europe.

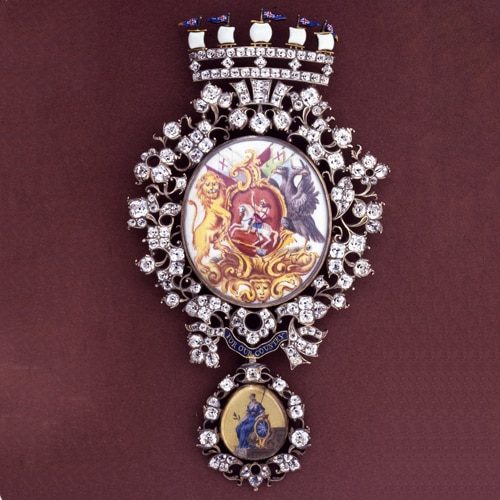

Georgian Silver

During the Georgian era, new silver finds in South America occurred on a very regular basis and production was booming. The fashion of setting diamonds in silver which had begun in the Baroque period became common. Diamonds were flowing into Europe in numbers never seen before from India and from 1727 on from Brazil where new deposits were discovered. Fine jewelry was often executed in gold with silver-topped front sides but items composed completely of silver certainly weren’t uncommon. The typical cut-down collet settings of Georgian jewelry are almost always composed of silver, complimenting the ‘ white’ color of the diamonds they would hold.

The manufacturing technique of die striking started to be used for jewelry in 1777. This method comprises the stamping and cutting of precious metal components with the aid of dies and presses or drop hammers. These components could then be assembled by hand to create a complete item. This relatively inexpensive manufacturing method heralded the first mass-produced jewelry lines and these items could be sold for far cheaper prices than handmade items. Naturally, the less expensive metals were used a lot in this process, and with silver being ported into Europe by the boatload large quantities of die-struck silver jewelry reached the markets.

Victorian Silver

The industrial revolution was booming during this period and of course, this had a vast impact on jewelry manufacturing. Silver was extensively used in stamping and die striking. This technique developed in the Late Georgian period and was perfected right through the Victorian era.

After Victoria and Albert bought Balmoral in Scotland in 1848 Scottish agate jewelry became a trend. These items were predominantly executed in silver in good Northern European tradition.

The Arts and Crafts sub-period, which was essentially a reaction to the above-described industrialization of jewelry manufacturing, at the end of the Victorian period, saw another trend in silver jewelry. The design of Arts and Crafts Jewelry was of primary importance. The intrinsic value of the metal and gemstones was really of secondary importance. In Arts and Crafts jewelry, cabochon cuts, usually bezel-set, were preferred over faceted stones and silver was preferred over gold.