Nineteenth-Century jewelry consisted predominantly of adaptations of earlier jewelry styles. It has been argued by some historians that a return to the past in jewelry design came from a singular lack of inspiration. Seen in retrospect, we now know that this return to the past, in fact, sprung from a renewed sense of national pride. These jewels reflected time periods of national achievement and symbolized all that was great in the history of European civilization. Two major styles emerged: Gothic (or Medieval) Revival and Renaissance Revival.

Throughout Europe, costume balls had become a popular form of entertainment. No expense was spared for these lavish events. The costumes were meticulously copied from relevant historical portraits and appropriate jewelry and accessories made to complete the look. A thousand Tudor and Stuart period portraits were displayed at the South Kensington Museum (later the Victoria & Albert Museum) providing inspiration to the jewelers working in the Revival styles. Some of this jewelry took on a popularity all its own. The ferronnière is an example of a historical fashion plucked from the past and worn boldly for some 20 years into the future.

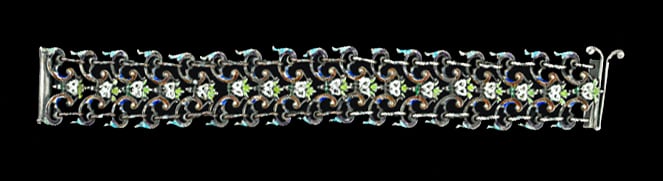

Gothic Revival Bracelet. Signed Geiss a Berlin.

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

Spurred by this swelling of national pride in many countries, a romantic movement swept Europe. A return to Gothic motifs in all areas of design flowed in on that wave, bringing with it a nostalgia for the aesthetics of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Each country embraced this nostalgia for different reasons. In Germany, the return to the Gothic style was used to unify their citizens against a common enemy: France. A Liberation Monument in the Gothic style by Karl Friedrich Schinkel was made in the foundry owned by Johann Conrad Geiss, famous for manufacturing iron jewelry. During the Franco-Prussian war, iron jewelry was distributed to patriots who turned in their gold jewelry to raise war funds. The post-war application of Gothic designs to iron jewelry, now known as Berlin Iron Jewelry, kept it fashionable for many years.

Gothic revival remained dominant in Germany but a Renaissance revival look also began to appear around 1850, slowly gathering popularity. Germans embraced this Renaissance aesthetic referring to it as alt-deutsch which became the style adopted during the rapid industrialization period after 1871 or the Gründerzeit (founding period). Alt-Deutsch crept into all aspects of design and all manner of luxury decorative goods were produced for the home with this medieval or Renaissance feel furthering the trend.

Holbein, claimed by both the Germans and the British, was an inspiration in the German alt-deutsch jewelry being produced and advertised as “Holbein Schmucksachen.”

The second category of alt-deutsch jewellery consists of jewels inspired by surviving sixteenth-century pieces. Given the number of princely collections in the new union of German states, the choice was huge: the collections of the house of Saxony in the Grünes Gewölbe in Dresden, the Bavarian royal collection in the Residenz in Munich, the Württemberg collection in Stugart, to name a few.1

Germany was known for its strong crafts guilds where apprentices trained to become goldsmiths. Commonly a graduation masterpiece was required to complete the apprenticeship and become a full-fledged goldsmith. Copying the work of Renaissance jewelers served to propel the aesthetic forward.

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

In France, the fashion for Gothic jewelry was set by the court. Gothic architecture, being restored throughout Paris at the time, was the model for Gothic jewelry being referred to as romantique. By 1830 the Louvre was in possession of significant collections of medieval items and in 1844 the Musée de Cluny opened, referred to as “the greatest monument to the Middle Ages.’’ 2 These all provided models for the newly popular Gothic style. In addition, the regime of Napoleon III during the Second Empire drew strongly from the Renaissance as being symbolic of France’s past glory. Painted enamel, including opaque enamel work en ronde bosse, was evocative of three particular styles: the Fontainebleau style of Henri II, Mannerism under Louis XIII and a Louis XVI style that accompanied a romanticizing of Marie-Antoinette’s life and death.

Sculptors played a major role in the design on jewelry in nineteenth-century France. They contributed models for use in three-dimensional sculptural figural designs. One of the premier jewelers in this tradition was François-Désiré Froment-Meurice. Employing sculptors, modelers, chasers, enamelers, goldsmiths and others in his shop he made unparalleled style romantique jewels. His work at the 1851 Exhibition earned him a Council Medal for his patinated silver historic French figural designs.

In the 1870s-80s a series of sixteenth-century jewelry designs and ornamental prints were re-published providing inspiration for French Neo-Renaissance jewels. Since the 1860s there had been a revival of painted enamel techniques (l’émail des peintres). Bright-colored enamels began to be used in layers creating a unique aspect to this style romantique.

It was during the year 1854, one evening…with his family gathered round the lamp, that he took the small panels of wood on which the delicate figures that made up the little group of the Toilette de Vénus were sketched out in wax. While the goldsmith’s fingers modeled these thin elongated figures…his mind determined every detail of the tiny scene; with the point of his brush he established the tones of the figures, the clumps of reeds from which they emerged, and the fruit and flower clusters which decorated the lower part of the pendant. Another evening we chose the pear-shaped pearls to hang from the jewel; we decided that the two Audouard brothers with their skilful fingers should construct the framework for the jewel; that Lefournier, still a formidable master despite his advanced age, should encase this beautiful pendant in the most vivid of enamel colours: that was the fashion then, in contrast to the deathly pale colours of enamels today.2

In Britain, they modeled Gothic jewelry straight from an album of Gothic tracery in the possession of the prominent jewelers, Rundell, Bridge & Rundell. Britain, however, never embraced Gothic as a national style. Drawing heavily from ecclesiastical metalwork, Gothic revival jewelry became tentatively linked to Catholicism and was therefore resistant to being overwhelmingly embraced. More popular were designs evocative of the Renaissance or Tudor style.

In 1856 an important suite of jewelry was commissioned for the Countess of Granville to wear as she accompanied her husband, the Ambassador Extraordinary and representative of Queen Victoria, to the coronation of Tsar Alexander II in Moscow. This suite, known as the Devonshire Parure, is comprised of seven ornaments which include a coronet, diadem, bandeau, comb, necklace, stomacher, and bracelet which were created from enameled gold and designed to exploit a collection of eighty-eight cameos and intaglios from the third Duke of Devonshire’s collection. The parure is believed to be the first piece made in the Holbeinesque style. After accomplishing its primary purpose, the parure was exhibited throughout England, ending up at the International Exhibition of 1872. It is still extant in its entirety and is on display at the recently refurbished Chatsworth House, home of the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire.

While these designs were neither duplicated exactly from the many paintings attributed to Holbein nor from the actual jewelry designs by him located at the British Museum, this jewelry was arbitrarily given the moniker “Holbeinesque.” Spurred on to popularity by orders for Holbein-style jewels from the royal family, Holbeinesque remained popular for another 30 years. By the 1862 Exhibition, the term Holbeinesque was being liberally used to describe any new jewelry pieces and all the prominent jewelers of the time were purveyors of the style. Devonshire-style settings – a vertical oval pendant centering a cabochon or gem-set motif became the model for Holbeinesque jewels.

British Museum.

John Brogden and Carlo Giuliano were two of the most prominent jewelers working in the Holbeinesque style and their jewelry could be found at the prominent firms of Howell & James, Harry Emanuel and Phillips and Hancock. In England, beyond the Holbein sketches at the British Museum, there were no collections of actual Renaissance jewelry to be used as models for this Renaissance style of jewelry. Attempts were made by some jewelers to utilize strapwork motifs in the form of scrolls, sometimes with a portrait or gem set in the center to achieve a Renaissance look. French figural jewels were another source of inspiration. It wasn’t until the International Exhibitions that this Renaissance and Gothic revival jewelry was widely seen by the public, and possibly even by other jewelers. The illustrated catalogs became pattern books, useful as reference and design inspiration. The South Kensington Museum regularly purchased articles of jewelry from various purveyors, including François-Désiré Froment-Meurice who worked in the French Renaissance style and put them on display to the public. The museum made several acquisitions at the 1855 Paris Exhibition that undoubtedly served as inspiration to all who viewed them.

Photo Courtesy of Christie’s.

German jewelers discovered by the late 1880s, much to their chagrin, that Renaissance revival jewels were no longer marketable. Fashions had changed and these heavy jewels no longer worked stylistically. In England, jewelry in the Renaissance Revival style continued to be made, principally by Giuliano into the 1890s. In France, the style began to morph into the precursor to Art Nouveau in the later part of the 1880s.

Thus from its beginnings as a return to a great age in France’s past, the Renaissance revival became a crucial stage in the development of Art Nouveau, providing ample evidence that Art Nouveau jewellers were not the first to turn jewels into objects of vertu.3

Sources

- Flower Margaret. Victorian Jewellery: South Brunswick, New Jersey: A.S. Barnes and Co., Inc., 1967.

- Gere, Charlotte and Rudoe, Judy. Jewellery in the Age of Queen Victoria: A Mirror to the World: London, The British Museum Press, 2010.

- Munn, Geoffrey C. Castellani and Giuliano: Revivalist Jewellers of the 19th Century. New York, NY: Rizzoli, 1983.